Liam Spender is a Trustee of the Leasehold Knowledge Partnership. Personally affected by the cladding scandal, Liam is a Solicitor-Advocate and Senior Associate at Velitor Law practising commercial litigation and arbitration in the City of London. Views in this article are personal and do not constitute legal advice.

By Liam Spender

Headlines about the cladding scandal appear daily. Bills running to tens of thousands of pounds, life changing amounts of money for most, are landing on the occupants of flats suffering serious fire safety defects.

When reading the comments under newspaper articles several questions often appear. How has this happened? Why doesn’t the leaseholder sue someone? Why hasn’t there been a class action? Why should the taxpayer pay? Why wasn’t this spotted before buying? Why is this not a case of buyer beware?

The lack of basic knowledge of leasehold law and property law among some government officials and some Members of Parliament dealing with legislation, such as the Fire Safety Bill, is alarming.

Robert Jenrick – once a City solicitor and today the Secretary of State responsible for addressing the fire safety scandal – has himself claimed that this is a case of “buyer beware”. In other words, that the people living in the affected flats are responsible for failing to foresee that bills of this size would be coming their way.

This piece sets out answers to some of the common questions outlined above, together with some simple information about the English law of property. It is not a substitute for legal advice. This area of law is complex and individual advice specific to your situation should always be taken.

What is a lease and how is it different from a leasehold?

Leases can be granted over various different types of land and property. Some leases are residential. Some are commercial. A lease given for an original term of 21 years or longer is a “leasehold” subject to special legal rules. Other leaseholds of shorter original terms exist but these are not subject to the same rules.

A leasehold is an estate in land. In English law there are three estates in land: freehold, leasehold and commonhold. Freehold and leasehold are the two most common estates in land.

A leasehold is a contract entitling the owner of that contract (the lessee, sometimes confusingly also known as the tenant) to exclusive possession of land for the term of the contract. That is provided the lessee sticks to certain promises (“covenants”) during the term of the lease.

Typical covenants include the obligation to pay ground rent and service charges during the term of the lease. Other common covenants include restrictions on noise outside certain hours and not operating businesses from the premises.

Is a leaseholder a tenant?

Leaseholders are often referred to as a tenant in the various laws containing the rules for the leasehold system. This is because a leasehold is always associated with a freehold. The owner of the freehold is the landlord of the leaseholder. In modern buildings there may be other landlords between the freeholder and the leaseholder. This is common in shared ownership buildings where there is a head lease between the freeholder and a housing association and in turn a lease between the housing association and the shared ownership leaseholders. The relationship in legal terms is one of landlord and tenant.

A leaseholder has many more rights and obligations than someone merely renting a flat. The rights include the ability to sell on the leasehold, to challenge spending by the landlord and to receive information about buildings insurance and other items charged via the service charge.

Even with better rights than renters, leaseholders are in the unfortunate position of having to pay to maintain a building but not having any say in how that building is maintained. As has become clear during the cladding scandal, freeholders are happy to be “long-term custodians” when it comes to collecting income from buildings, but not when it comes to meeting any of the costs of that custodianship.

What are the common parts?

In simple terms, the common parts are any part of the building that is not subject to someone’s leasehold (you may hear the terms “demise” or “demised to the lessee” which is the way the extent of the leaseholder’s space is defined).

The common parts typically include the roof, the external walls, the corridors and accessways, the cables and pipework outside of a flat, the fire alarm and fire safety system, the communal entrances, the lifts and stairways and the grounds outside the building.

So leaseholders don’t own the ground the building stands on?

Commonly it is said leaseholders do not own the building or the land it stands on. This is an oversimplification. Whilst the freeholder does own the ground and the building itself, the freeholder’s ownership rights are restricted for the term of the lease. The freeholder may only exercise its rights in accordance with the terms of the lease. The freeholder’s rights are so restricted that a freehold for a large apartment building may be worth as little as the market value of only one or two flats in the building.

A leaseholder has the right of exclusive possession of the leased property for the term of the lease. That includes the right of support from the ground below. It also includes the right to pass over any land on the site necessary to reach the leased property.

For as long as the leaseholder carries out his covenants under the lease, those rights cannot be taken away from the leaseholder.

For example, if a freeholder decided to permanently block off the access to a leaseholder’s property to redevelop the land around the building, the freeholder would not be able to rely on his rights as the owner of the land to justify the action. The freeholder would most likely have to pay significant damages (money) to the leaseholder in those circumstances.

One of the main problems with leaseholds, being complicated contracts, is that the terms of such contracts give freeholders the power to make decisions about what happens to the common parts of the building and the land outside the building. Another common abuse of the leasehold system is that landlords – and the professional agents appointed by landlords to manage the common parts – charge leaseholders fees and commissions that are often difficult to see and hard to challenge.

Why do we have leasehold?

Leasehold is product of the feudal system. In mediaeval times all land belonged to the monarch. The monarch granted rights in land to others as a reward for service, or in exchange for taxes and supplying soldiers when demanded. The ownership of land and rights in land were central to the mediaeval society and the mediaeval economy.

The feudal system was gradually reformed over hundreds of years. Some aspects of it persisted until 1925, when the Law of Property Act abolished all remaining feudal interests in land and created the modern system of freeholds and leaseholds. Commonhold was added in 2002 but has not been adopted widely.

Leasehold evolved because in English property law it is, except in rare cases, impossible to make a positive covenant (a promise to do something or to pay money toward something) move from one freehold owner of land to the next. That would be a problem if flats had to be sold as freeholds. The freehold could change hands and the new owner would not subject to the positive promise to pay for the upkeep of the common parts. The leasehold system was designed in part to address this inability to bind future owners to promises made by previous owners. It would also be possible to address the issue by a change to the law of freehold covenants, but that has not yet been achieved.

The Victorians perfected the model of leasehold to help build and sell their mansion blocks of apartments. This enabled the landowners to keep their interest in the land (via the freehold) whilst also enabling others to take an interest in the same land (via the leaseholds).

England and Wales are today the only places in the world that retain the leasehold system. Other countries have adopted a system where the people who buy properties in an apartment building have a share of ownership, eliminating the freehold/leasehold distinction. For example, Australia moved to its system of strata plan title in the 1960’s. England and Wales did develop commonhold on the basis of the Australian system, but hardly any commonhold developments have been built.

In recent times, leasehold has become deeply unpopular as a result of the fact that a market in ground rents has been created. Investors have been able to assemble large portfolios of leasehold properties and they collect grounds rents, insurance commissions, administration fees and other mark-ups on services provided to leaseholders as a form of investment income.

What is caveat emptor?

Caveat emptor is a neo-Latin legal maxim (general principle). It is commonly translated as “let the buyer beware”. In practice it means that a buyer is under a duty to take care to learn all that he can reasonably learn before buying something. If he does not, then he will not have any recourse against the seller if the goods turn out to be defective later.

In the case of most consumer goods and services sold today, the principle of caveat emptor has not only been abolished but reversed. The most recent revision of the law was the Consumer Rights Act 2015. The modern law makes the sale of consumer goods and services subject to automatic terms that goods will be fit for the purpose for which they are supplied or that services will be performed with reasonable care and skill. Buyers have legal rights to demand the repair or replacement of defective goods, or even a full refund. Sellers are also subject to automatic rules that they have a positive obligation to disclose certain kinds of information about their products or services and consumers’ rights in relation to those products and services.

Unfortunately, the principle of caveat emptor remains in force when it comes to buying and selling property, both residential and commercial.

The main exceptions to the principle are where there has been outright fraud, misrepresentation or negligent misstatement.

Fraud is a crime. Misrepresentation and negligent misstatement are civil claims.

A clear example of fraud would be marketing a property for sale without actually owning that property.

Misrepresentation is a seller deliberately, recklessly or negligently mis-describing the state of the property to persuade the buyer to buy it. A misrepresentation need not be in response to a direct question from the buyer. An example of misrepresentation would be covering up a damp or mould problem by painting over it without addressing the root cause of the issue.

Negligent misstatement is where someone asked a direct question or is under an obligation to provide accurate information deliberately or carelessly provides inaccurate information. Negligent misstatement covers parties other than the seller, such as a managing agent or a landlord in relation to information either of them provides about a leasehold property. Negligent misstatements may include failing to provide information about works planned for the property in the near future.

How does caveat emptor apply when buying a property?

In the residential context, caveat emptor means buyers must take care to learn what they can reasonably learn about the property before buying it. This is why official records are searched and enquiries are made of the seller as a part of any residential property transaction. Investigations are also made to establish whether there is any evidence of poor ground conditions, land contamination or flood risk.

Buyers will also typically engage a surveyor to value the property and to report on any obvious defects. In some cases, particularly where the property is very old or has unusual features, surveyors will also be asked to perform intrusive inspections and other studies and surveys to help establish whether any extensive works are required.

Note that what caveat emptor does not mean is that buyers are responsible if the government decides to change the law at some point in the future. All commercial transactions take place on the basis of the law as it stands on the day of the transaction.

As explained below, the government has a large share of responsibility for the cladding and fire safety costs being demanded of leaseholders. Not only have successive governments failed to regulate the sector properly, the current government has retrospectively imposed higher requirements on buildings via its Advice Notes.

Don’t local councils perform building inspections to make sure buildings are safe?

No. Building control services were partially privatised from 1985. At the same time, Building Regulations were simplified so that they only enunciated general principles rather than detailed rules.

Local councils have to compete with private building control bodies (Approved Inspectors) for work inspecting buildings. Developers decide whether to use the local authority inspectors or to employ an Approved Inspector. Once an Approved Inspector is appointed, a local authority has little – if any – oversight over how the inspections are being performed.

How have we ended up with these cladding and fire safety issues? How could buildings have been built with this cladding and/or with fire safety issues? How long has this been going on?

The simple answer is that cladding has been permitted by vague Building Regulations and inadequate regulatory supervision. This has been going on since the early 1990’s.

The evidence emerging from the Grenfell Tower Inquiry to date is that the government has been aware since at least 2014 that the industry was not following the government’s interpretation of the Building Regulations. Some argue that the government has known of the dangers of inadequate regulation since 2009.

The use of combustible materials in external walls is something that has grown progressively more widespread since 2000. As Dr. Jonathan Evans explains here: https://www.law.ox.ac.uk/housing-after-grenfell/blog/2019/12/height-confusion governments first began to water down the requirement that materials on high-rise buildings should be of “limited combustibility” from around 1992. Successive revisions of the Building Regulations further confused the applicable requirements, leading to a situation where even highly flammable material such as polystyrene were deemed appropriate to incorporate into the external walls of high-rise buildings.

These changes, coupled with the de-regulation of building control from 1985 onward, has proven catastrophic.

Is this something limited to the outside of buildings? Aren’t there problems inside as well?

Yes. Inspections conducted on external walls have revealed that many buildings also suffer from internal fire safety defects. A central principle of building blocks of flats is that they should built in such a way to prevent smoke and flame spreading from one part of the building to another. This is called compartmentation. Compartmentation rests on building in features such as fire breaks and putting fire stopping material around the holes left by pipes and cabling. Effective compartmentation is what underpins the policy of “stay put” in the event of a fire.

It has been discovered that as a result of shoddy construction many thousands of buildings are in fact not adequately compartmentalised. This has led to the imposition of 24 hour “waking watches” to support a policy of “everybody out” at the first sign of fire. These costly interventions are unsupported by any evidence that they would actually save a single life in the event of a fire.

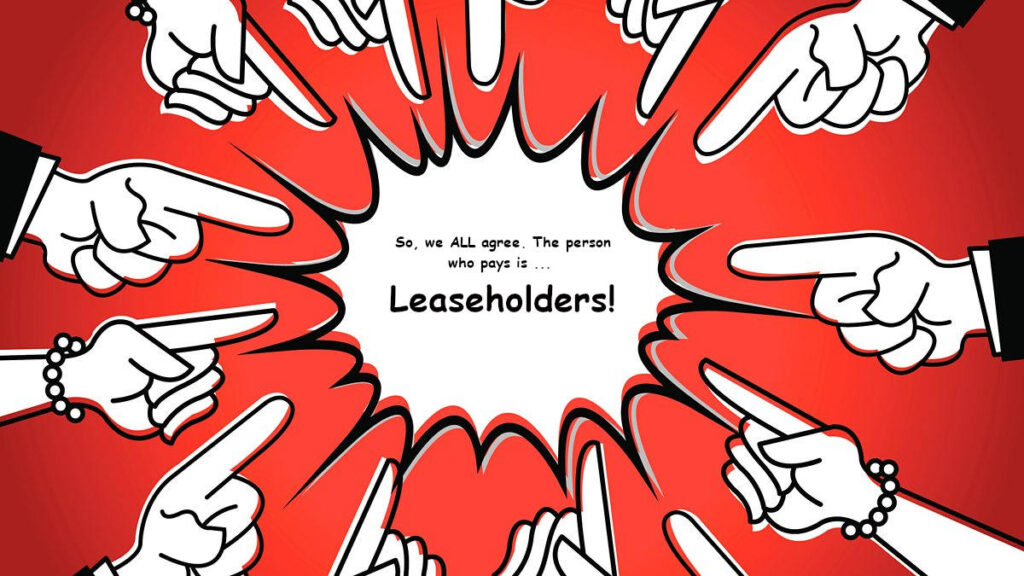

Why are leaseholders paying for this?

Earlier we looked at the distinction between the common parts and the demise. A leaseholder is responsible for the costs of everything in the demise. A leaseholder is also responsible for paying a service charge for the maintenance of the common parts.

As explained here: https://www.law.ox.ac.uk/housing-after-grenfell/blog/2018/07/green-quarter-decision the service charge provisions in some leases have been interpreted as requiring leaseholders to pay for the costs of fixing defective cladding and internal fire safety defects. No leaseholder could have foreseen these costs. These costs range between tens of thousands and hundreds of thousands per leaseholder.

Not all leases permit these types of costs to be recovered from leaseholders. The government and several politicians have commented that they believe leaseholders are the only parties who can be compelled to pay. This is not true in all cases. The government knows this. That is why it is proposing to introduce a new Building Safety Charge to remove any doubt that it is leaseholders’ responsibility to pay this type of costs.

Why aren’t freeholders paying for this?

Freeholders, despite claiming that they are essential to administration of leasehold properties, have largely refused to pay. That is even when the freeholder is the original developer, as is the case at Ballymore’s New Providence Wharf and Galliard’s New Capital Quay developments in London.

Freeholders claim that they are as innocent as leaseholders when it comes to buildings with cladding and internal fire safety defects. They claim they should not have to pay for defects that could not have been foreseen. Despite the defects being unforeseen and unforeseeable, freeholders have nevertheless insisted on holding leaseholders to the letter of their leases in making leaseholders pay.

Aren’t these costs, however large, just a feature of owning a property? Isn’t this just the leaseholders’ bad luck?

No. Buying a property involves taking on the risk for maintaining and repairing that property. The issue is whether that maintenance and those repairs are foreseeable or whether they arise as a result of the building not being constructed properly, or the government moving the goalposts.

Needing to replace the windows or the roof are foreseeable repairs that are the responsibility of every property owner. Needing to spend money on the upkeep of a property is also a foreseeable matter that goes along with home ownership. Neither case covers what is happening to leaseholders.

Leaseholders are being forced to pay for the consequences of widespread failures of builders and regulators. The buildings in which they live have not been constructed properly. This is an industry wide failure not limited to a few buildings.

Leaseholders are also being asked to pay for the consequences of a retrospective, back door changes imposed on them by the government since 2017 via Advice Notes.

Should the taxpayer pay?

There are strong arguments that the taxpayer should make a large contribution to the costs. This is not only because of the failure of successive governments to regulate the building industry properly. It is also because the government has moved the goalposts.

As explained here: https://www.leaseholdknowledge.com/government-use-of-extra-statutory-powers-has-made-the-cladding-crisis-far-worse-than-in-australia-or-possibly-scotland-writes-lkp-trustee/ it is also because the present government has worsened the situation by imposing higher standards on buildings below 18 metres than those embodied in current Building Regulations. The standards imposed on buildings above 18 metres were also never explicit in Building Regulations prior to 2018.

The difficulties of getting justice over cladding, even in Australia:

The Lacrosse Apartment Fire: Obtaining Justice for Dangerous Cladding

The Lacrosse Fire and its significance in Australia and the United Kingdom On 24 November 2014, an incorrectly extinguished cigarette ignited with the timber top of a balcony of the Lacrosse residential apartment tower in Melbourne, Australia. The fire quickly spread to the nearby external aluminium composite panel (“ACP”), which contained a 100% highly combustible polyethylene core.

Are there alternatives to the taxpayer paying?

Yes. If the government chose it could collect the money from the building industry, cladding manufacturers and building inspectors/Approved Inspectors and others via a levy system.

The LKP itself has proposed one such model, which is here: https://www.leaseholdknowledge.com/as-17-of-cladding-leaseholders-consider-bankruptcy-lkp-funding-proposal-offers-alternative-to-successive-crises-facing-flat-owners/.

Won’t the Grenfell Inquiry sort all of this out?

No. The Grenfell Inquiry is an investigation into what went on at Grenfell. It is not going to apportion blame for cladding installed on other buildings.

The Inquiry is likely to make findings about product suppliers, regulation and fire safety. Whilst these recommendations will be of use generally, the findings will not create any new legal claims or bring back any claims which are already time-barred.

Isn’t the government going to limit leaseholders’ costs to £50 a month?

No. The government proposes to force leaseholders living in buildings between 11 and 18 metres tall to accept loans to pay for the costs of removing cladding. Those loans are said to be limited to £50 a month. No details have yet been published.

Importantly, even if there are loans to some leaseholders, that will still mean leaseholders paying in full for the costs of removing cladding plus interest, merely spread over a longer period.

Leaseholders will still have to pay in full for any non-cladding defects, which may mean they have to find tens of thousands of pounds before being able to access any loan.

Finally, leaseholders will have to continue to pay for the costs of any waking watch, fire alarm upgrade or increased building insurance regardless of the loan. All of those costs will total considerably more than £50 a month.

Leaseholders in buildings under 11 metres will not have any cap on their costs at all, whether cladding related or not.

Leaseholders in buildings above 18 metres will have to pay for non-cladding costs, which will be uncapped, but may receive a grant to cover their share of the cost of replacing cladding.

Why wasn’t this picked up before buying?

It is impossible to detect these problems before or after sale. Identifying cladding requires a specially qualified surveyor. Sometimes identification is only possible after testing samples. Gathering samples involves removing panels and cutting out squares for testing. Leaseholders have no ability to do that without the freeholder’s consent.

The internal fire safety defects also require properly qualified surveyors and engineers to inspect the building. This also involves cutting holes in walls to check whether fire breaks and fire stopping are installed correctly. Again, this process requires the freeholder’s permission.

Indeed, in relation to buildings under 18 metres tall, the Building Regulations still permit the exact same cladding and insultation that was used on the Grenfell Tower to be applied. The government has not changed the Building Regulations, but is nevertheless forcing the people living in those buildings to pay to have cladding removed which is still permitted by law.

Why isn’t this covered by buildings insurance?

Leasehold buildings insurance is event-based cover that is only triggered when a building sustains damage as a result of events specified in the policy. Events of this sort are not covered by standard buildings insurance. The same would be true in relation to buildings insurance covering individual houses.

What is happening here is that latent defects, which were present when the building was completed but not obvious at that time, are being discovered. Arguably, the government’s own Advice Notes have compounded this problem by reclassifying certain external wall materials as dangerous when these were, and in some cases still are, permitted by Building Regulations at the time.

Don’t buildings have warranties for this kind of thing? Why aren’t the warranties covering these costs?

New buildings are often sold with cover for latent defects. This cover is supposed to respond to events that buildings insurance would not cover. Cover comes in the form of a warranty (a promise to pay) or an insurance policy.

In practice, the warranty and insurance providers are refusing to pay on the basis that the defects in question are not covered by the warranties and insurance policies in place. Even when policies do pay, they may not cover all costs sustained by leaseholders, as explained here: https://www.leaseholdknowledge.com/new-capital-quay-litigation-continues-with-concern-that-repairs-may-still-not-meet-building-regulations/

Common justifications for refusing to pay are that the defect in question does not result from a breach of Building Regulations or that the defect does not cause a present or an imminent risk to life.

The insurers and warranty providers argue that the building complied with Building Regulations in force at date of completion. The fact that new knowledge, or government action via Advice Notes, means the building may not comply with Building Regulation is not something that triggers the policy.

The insurers and warranty providers argue that if the buildings were an imminent or present danger to life then the building would have been evacuated. An alternative argument is that buildings with a waking watches cannot be an imminent or present danger to life because the waking watch has removed the risk.

A further complication is that latent defects warranties or insurance policies are written for time limited periods, typically 10-12 years from completion. If claims are not made within the time allowed then they cannot be made later. Leaseholders are learning that by the time they realise there is a problem the cover is no longer available because time has run out.

Why can’t leaseholders sue the surveyor?

Leaseholders who used a surveyor are unlikely to have a claim. A surveyor would owe duties under contract to perform the survey with reasonable care and skill. Those duties are unlikely to extend to identifying cladding issues or internal fire safety defects, such as missing fire breaks.

Identifying the type of cladding installed on a building is a specialist skill. It often also requires removing panels and sometimes sending samples for testing. Even if a surveyor had the necessary skills, it is unlikely that a freeholder would give permission for such intrusive work to carry out.

Identifying internal fire safety defects also requires cutting into walls and falls and performing tests of equipment installed. Again, these are specialist skills that would most likely require the freeholder’s permission in order to be exercised.

Even if a claim against a surveyor were possible, the law deems that a survey is only a source of information for a buyer, not a recommendation to proceed with a sale. Under that principle (sometimes referred to as the SAAMCO cap), a surveyor’s liability would most likely be limited to the consequences of providing incorrect information, so most likely no more than the difference the price the flat would have achieved if the cladding had been identified and the price paid. For these purposes a “zero valuation” is unlikely to be applied. A “zero valuation” is a means of indicating uncertainty about how to value a property, not that the property is worthless.

Last but not least is limitation. A surveyor is only liable under contract for 6 years from the date of the breach, which at the latest would be the date of the surveyor’s report.

Claims in tort (that the surveyor owed a duty of care) the limitation rules are different. A tort claim requires that the claimant sustains damage before the claim is accrued (complete) and the time limits for making that claim start to run.

In transaction cases, the damage is deemed to be sustained on the date the transaction is complete. When buying a house this is regarded as the date of exchange of contracts, when the buyer becomes legally bound to complete the purchase. Time to make a claim runs from that date.

A separate limitation rule for tort claims is that where a claimant has sustained damage but is not aware that he has a claim, then he has three years from the date he becomes aware of the facts of the claim to make that claim. This is subject to an overall limit that a claim must be made no later than 15 years from the date of the negligent act.

Many leaseholders are therefore out of time to make claims.

All things considered, it is highly unlikely that any claim against a surveyor would succeed. Even after Grenfell and the heightened concern around cladding, it is likely any surveyor would still escape liability if he pointed out that cladding and fire safety was not something covered by the survey and that the buyer should satisfy himself that the building did not suffer from any cladding or fire safety issues before completing on the purchase.

Why can’t leaseholders sue their solicitors?

Solicitors are in a similar position to surveyors, for the reasons described above. It is unlikely that any solicitor would have the necessary technical or factual knowledge to identify and to advise on cladding and fire safety issues.

The same rules around limitation and the potential SAAMCO cap on any damages also apply in relation to solicitors. As with surveyors, it is again highly unlikely any claim would succeed. As with surveyors, a solicitor would most likely escape liability if he drew the buyer’s attention to the need to check fire safety and cladding issues before completing on the purchase.

Why can’t leaseholders sue the developer?

Claims against developers are the most likely avenue for leaseholders to be able to recover the costs they are incurring in relation to cladding and fire safety defects. These are, however, difficult claims and subject to strict time limits.

There are two potential claims against a developer. The first applies only where a property was bought off plan. The second is available to all leaseholders.

Leaseholders who bought off plan are likely to have a contract with the developer. Whether or not the contract contains terms saying that the building would be constructed with reasonable care and skill and that it would be fit for habitation, the argument would be that such terms are to be “read into” (implied) into that contract. If the building had cladding and fire safety issues then it is arguable that those terms were broken. That would entitle the leaseholders to claim for money (damages).

There is a six-year time limit for bringing claims under contract. The breach of contract will have occurred at the latest on the date the building was completed, although this date may be earlier depending on the terms of the contract in question. Time runs from the date of the breach, whether the defects were known or not. The period is 12 years if the contract was made by deed.

A developer would most likely owe a duty of care (a duty in tort) similar to that in the contract. The same principles as in relation to surveyors (explained above) apply in relation to time limits for bringing such claims. The six year period for bringing a claim in tort is likely to run from the date the building is completed, although a claim in negligence from the original purchaser is possible up to 15 years from that date.

The second potential claim against a developer is under the Defective Premises Act 1972. This is a claim that the standard of work on the property rendered it “uninhabitable”. For the purposes of this claim “uninhabitable” means impossible to occupy without serious inconvenience, rather than being impossible to live in at all.

Claims under the Defective Premises Act are subject to a strict six year time limit. The time limit applies whether the claims are known or not. The six years runs from the date the building is completed.

In some cases, the original developer may have given something called a collateral warranty to the freeholder. This often occurs when a social housing association buys a block of flats. A collateral warranty is a contract that gives the freeholder rights against the parties involved in construction. Collateral warranties are typically made by deed. If there are defects in the building, it may be possible to claim against the developer and others involved in construction via the collateral warranty. Claims could be made up to 12 years from the date of breach. The date of breach, at the latest, will be the date the building is completed. This is not something leaseholders would be able to pursue directly, but it may be a potential route to recovery in some buildings.

If any of the claims described above are not brought within the time periods described above then they are lost forever.

In a large number of cases where buildings are more than six years old, leaseholders are finding that they are out of time to bring claims. Even where claims are still possible, leaseholders are running into the legal rules limiting liability of those concerned.

Why can’t a developer be sued in negligence if I did not buy off plan?

It is not possible to claim economic losses (losses which are measured only in terms of money) against someone unless there is a specific duty of care assumed by that person toward the claimant.

In the case of leaseholders, the losses they are sustaining are deemed to be economic losses and therefore not recoverable from the developer.

A developer who sold a property off plan is likely to have a duty of care to the original buyer and to the original buyer alone. That will sit alongside any duties under the contract for the off plan purchase. A developer does not owe a similar duty to the second or later purchaser.

Why can’t leaseholders sue the cladding manufacturers?

Cladding manufacturers do owe a duty of care. Product manufacturers also have legal responsibilities under the Consumer Protection Act 1987.

Cladding manufactures are unlikely to owe any duty of care to avoid causing financial losses to people who did not deal directly with them. This is for the reasons explained above in relation to surveyors and other professionals. The same difficulties with time limits (limitation) also apply.

Cladding manufacturers are likely to owe duties under the Consumer Protection Act 1987. This law provides that the manufacturers of products owe duties to ensure that they are safe to use. If a product can be shown to be defective and to have led to personal injury or property damage then the manufacturer is liable. However, the Consumer Protection Act 1987 does not cover economic losses (losses measured only in terms of money). The costs being sustained by leaseholders are deemed to be economic losses and are therefore not recoverable.

Limitation periods under the Consumer Protection Act are also strict. Claims must be brought within 3 years of the date of any injury or loss (where recoverable), or within 3 years of the date of discovering the claim, if later. No claim may be brought more than 10 years after the product was first supplied to the market.

The Consumer Protection Act 1987 is therefore unlikely to be of any use to a leaseholder who does not suffer personal injury or damage to property as a result of a fire fed by defective cladding. The limitation periods are also likely to preclude many claims.

Contractual claims against cladding manufacturers are also impossible because leaseholders have no contract with the manufacturer. In any event, a claim under contract must be brought within six years of the date of the breach.

Why can’t leaseholders sue the architect?

Architects performed their work under contract for the developer. The architect would also have owed a duty of care to the developer.

As the law currently stands, it is unlikely that an architect would be found to owe any duty of care to avoid causing economic losses (losses measured only in money) to leaseholders living in the completed building.

The same problems with limitation discussed in relation to surveyors and solicitors would also apply even if a claim against an architect were possible.

Why can’t leaseholders sue the Building Inspector/Local Authority/Approved Inspector?

The law in England since 1990 has been that a local authority building inspector owes no duty to prevent a property buyer from incurring economic losses as a result of the inspector’s failure to perform building control properly.

The exception to this, which may be made explicit in any litigation in relation to the Grenfell tower fire, is where the building control failures can be shown to have led to personal injury or death of any resident of that building.

The Court of Appeal recently confirmed that the same protection applies to private Approved Inspectors performing building control functions (see answers above).

As the law currently stands the last line of defence in ensuring that a building is being designed and constructed according to Building Regulations, and who signs certificates to that effect, owes no responsibility if the building turns out to be defective and the occupants have to pay to correct those defects. This has been known for over 30 years. Successive governments have failed to do anything about this striking gap in the law.

Why can’t leaseholders sue the government?

There are a lot of headlines about people who have “sued the government”. Usually these refer to judicial review claims. A judicial review involves a judge looking at a decision made by a public body, which may be the government, a hospital, a local authority or a wide range of other public bodies. The judge examines the process and evidence used to reach the decision. The judge decides whether or not the government has followed certain legal rules and principles in making that decision. If not, the judge has the option of quashing (overruling) the government and directing that the decision is made again. Rarely will the judge substitute his decision for that reached by the government.

Judicial review claims also often involve seeking a mandatory order (an injunction) requiring the government to take (or not take) certain steps, for example to not to allow a third runway at Heathrow, or not to allow a building to go ahead.

There is no automatic right to seek a judicial review of a government or local authority decision. The court’s permission must be obtained. There is a strict three-month time limit for making applications for permission for judicial review in the High Court. Different types of applications may have shorter time limits, perhaps a few weeks in some cases, such as planning and immigration appeals.

Most judicial reviews fail. Ministry of Justice statistics show that only around 20% of High Court judicial review cases get permission to proceed to a hearing. On average, only 3% of such cases result in a decision in favour of the claimant (https://www.gov.uk/government/statistics/civil-justice-statistics-quarterly-july-to-september-2020).

There are different figures and success rates for judicial reviews related to planning, immigration, benefits and other matters handled outside the High Court.

A judicial review on its own does not enable a claim for financial losses incurred as a result of the action being challenged. That is unless the government has also breached a duty or a contract that would entitle the claimant to seek losses separately from the judicial review.

Nor is there any general right to recover large amounts of money even if the claimant can demonstrate that the government has infringed the Human Rights Act. Damages awarded under the Human Rights Act follow precedents laid down in this country and by the European Court of Human Rights (a court separate from the European Union and which was founded as part of the 1948 European Convention on Human Rights). The damages (money) paid for a human rights violation is rarely more than a token amount.

In the case of leaseholders and cladding, as things currently stand it is difficult to see any claim against the government that is likely to produce substantial damages (money) for leaseholders.

Can leaseholders sue anyone?

The plain, unfortunate fact of the matter is that once a building is more than 6 years old it is unlikely that a leaseholder has a viable legal claim against anyone. That is a result of the limitation periods and legal reasons described above. It may be possible to claim under a building warranty, but these typically only last 10 years from completion.

As explained here: https://www.leaseholdknowledge.com/new-capital-quay-litigation-continues-with-concern-that-repairs-may-still-not-meet-building-regulations/ litigation is also a costly, long drawn-out and risky affair. The costs of litigation would have to be met by leaseholders, either in the form of losing a share of any money awarded at the end of the case or by paying fees as the case went along.

Even if there is a viable claim there needs to be a deep pocket to pursue to make the claim worthwhile. If there is no-one able to pay a judgment in favour of the claimant then there is no point pursuing the claim.

Why hasn’t there been a “class action”?

A “class action” is not possible under English law. Under the federal law of the United States, it is possible for one party to bring a claim as a representative of all members of people in the same situation (the “class”). If a court is satisfied that the class exists and that the representative has an arguable claim then it will allow the matter to go to trial.

Importantly, the law in the United States allows class actions to be brought on the basis that claimants must opt-out if they do not wish to be involved. This makes it much easier to bring this type of claim.

In England there is no equivalent to a class action for general litigation, although there is something equivalent for certain types of competition law claims. In the case of general litigation, the court rules give a judge discretion to allow a group of claimants with a common interest to argue their cases together under a Group Litigation Order. This does not work in the same way as a class action.

Starting any litigation requires demonstrating that there is a claim. For the reasons explained above, most leaseholders living in buildings more than 6 years old are unlikely to have any viable legal claim against anyone, unless there is a building warranty in place. If no member of a group has any claim, then there can be no group claim.

A group claim is also difficult because leaseholders are not dealing with the same type/s of issue/s caused by the same defendant/s. Every building has different issues and was built by different builders. A group claim is only possible if there is sufficient commonality between the claimants to enable the court to decide the issues for all claimants. The position of leaseholders is very different from, for example, the owners of RBS shares during the 2007-8 financial crash, or the owners of Volkswagen cars employing “defeat devices”, which are examples of legal and factual issues common to many claimants and only one or two defendants that could be tried via a Group Litigation Order.

As regards cost, litigation at scale is expensive, particularly in a case involving thousands of parties and thousands of buildings. These days such litigation is funded on the basis that the winner will give up a share of any damages (money) awarded in exchange for a third party providing funding. The funding may come from a law firm itself or from a specialist third party litigation fund. Given the different legal and factual issues involved, multiple different defendants and multiple buildings, it would be difficult to attract the necessary funding to pursue a case even if the claimants had claims they could pursue in this way.

What can leaseholders do?

This is ultimately a political problem. It does not require a new law or a legal case to solve this problem. It requires only a political choice.

Successive governments bear responsibility for decades of regulatory failure. The current government bears responsibility for the costs forced on to leaseholders via its Advice Notes. The construction industry bears responsibility for failing to construct buildings with proper internal fire safety measures and flammable cladding. A host of different professionals are responsible for designing and approving buildings constructed in this way.

There are no easy legal ways of solving that problem. The only legal steps the government has taken to date is to propose to remove any doubt that leaseholders are to pay these costs by changing the law to make them solely and explicitly responsible for these costs.

As has already been demonstrated in Australia, the only way a problem like this is solved is by the government stepping in and allocating responsibility, providing up-front funding and collecting contributions from those responsible. Scotland is about to adopt a similar approach.

So why not the same in England and Wales?

Government’s use of extra-statutory powers has made the cladding crisis far worse than in Australia (or possibly Scotland), writes LKP trustee

Government’s use of extra-statutory powers has made the cladding crisis far worse than in Australia (or possibly Scotland), writes LKP trustee

The heart of the problem is the RICS. Surveyors fall into two categories – valuers and valuation is a sort of skill, and measurers [QS]. Neither has any engineering technical competence beyond average common sense.

The value of property in UK compared to Europe is quite unbelievable: e.g a large five bedroom house in smart suburb of Strasbourg is worth less that a three bedroom estate house in Cathcart, Glasgow. It is the RICS who have cranked prices up since the 1960’s. The rise in house prices in the 1970’s and 1980’s is simply staggering.

So the PROFITS of building blocks of flats is outrageous. Is this not an argument for making developers pay for the great British cladding cockup ?

Next is how can a so called “Professional” not be responsible when they get involved in matters beyond their comprehension ? Simply put it is negligence.

In the end it often all comes down to fees – what a property manager or developer can get away with …. RICS, ARLA, ARMA, IRPM et al are just coverup and self protection operations.

In my view it should always come down to contracts. And people forget that the conditions of the lease between lessor [freeholder] and lessee [owner] are incorporated mutatis mutandis in the contracts between the freeholder [whose shareholders are often owners] and the property manager [unqualified RICS etc], and also between the property manager and accountants CERTIFYING charges [a complaint on this basis currently with the ICAEW – the certification process must include an audit process].

When it comes to health and safety, the government is capricious:

Fire Risk.

The DLGC controls everything; government ignored views of fire inspectors and nobbled the building regulations.

Speed humps.

Speed humps removed and replaced with a system of 20-mile an hour limit enforced with fines. So, it is now easier for a careless driver to hit a child. Done for the convenience of the bicycle crowd.

Covid.

Total health fanaticism order of the day right now.

No consistency?

As an existing building, Grenfell Tower was “improved” with cladding. The risks associated with cladding have been an open secret to many, including part of the judiciary within the United tribunals Structure. The construction industry, the health and safety crowd and the fire inspectors knew about cladding risk. The subject had arisen at a number of fire incidents prior to Grenfell Tower. It was generally felt that building regulations were nobbled for the benefit of the climate-change mob.

There are surveyors, who sit as judges at the Upper Tribunal/Lands Chamber as as panel members or chairmen on the trial panels at the 1st tier property tribunals. A qualified surveyor does not require evidence to see that he is dealing with a Christmas cracker. One supposes that there are leaseholders who raised the issue of cladding at some court hearings. In particular there are many Local Authority landlords, such as Royal Borough of Kensington and Chelsea, who have danced to the tune of the DLGC over the years. Some ex-Local Authority Leaseholders would have pointed out:

1. Climate-change related housing policy is not rechargeable under a lease because there is no lease provision to save the Maldive islands etc. The levels of expenditure involved are not financially justifiable in terms of benefits to the lessee and the demise etc.

2. There was no genuine consultation because the policy was simply imposed on leaseholders by central diktat etc.

3. Cladding is dangerous and unacceptable etc.

No doubt, leaseholder liability for such invoices has been rubber-stamped on many occasions by a compliant judiciary. It is therefore worth inspecting the record of trials to see when such matters were raised. Sir Keith Lindblom was running the whole show prior to his recent elevation. He is no doubt a person of interest, who may assist with inquiries. Martin More-Bick has successfully conducted a damage-limitation operation to ensure that judicial complicity is not within the remit of his Inquiry. The public are therefore reliant on the police and Parliament to complete the Investigation.

PS. For anyone willing to listen, climate change does not exist in the way our government says it does.

All read with a large degree of indigestion especially as to the PS !

In what way does climate change not exist as the govt. says?

Kyoto was the block on which Mr Blair pushed the Uk to reducing carbon emissions from buildings. But no ones to blame here so taxpayers have nowhere to hide…

David, CO2 is only an insulator for infra -red. It is not an actual heat source. Yes, global average temperature is increasing. But, is it temperature at night, temperature at the day maximum which increases? The theory of planetary temperature equilibrium and associated theory of global warming are silent on that question. CO2 is a transient nocturnal insulator that raises night-time minimum temperature. Daytime temperatures do not change. And CO2 is only operative as a nocturnal insulator in the presence of H2O.

Think of it this way: all the dwarfs are disappearing. So average height of men increases. No individual man gets taller. So, no need to buy a new car. Be careful of averages.

And remember the Iraq war! Blair should have been sick as a parrot with bird flu, when he got to Iraq and could not find any weapons of mass destruction. He is the first king of England to go to war by mistake.

A good article. Politically, the government should foot the bill for remediation. Legally, the deficiencies in English land law are again exposed: the lack of responsibility for consumer rights that we nowadays expect.

I respectfully suggest an edit:

“That is a problem when leaseholds can change hands and the new owner is not subject to the positive promise to pay for the upkeep of the common parts.” The writer surely meant to type “when FREEHOLDS can change hands”. The problem lies in freehold positive covenants. The Law of Property Bill 2016 could have helped to fix the deficiency. It was in the Queen’s speech but ran out of parliamentary time. Freehold flats were tried out in the 1950s but became problematic, apparently.

Thank you. Yes, I did mean to write the inability to enforce positive freehold covenants explains in part the need for leasehold. I have amended the post.

“It would also be possible to address the issue by a change to the law of freehold covenants, but that has not yet been achieved.”

And / or adopt best practice as used elsewhere for communal living, a good Commonhold system may solve this ? Although as some say, issues in converting existing leasehold buildings to Commonhold

Thank you Liam for an excellent and informative article.

So what I’ve learned is that any kind of professional service associated with buildings is just a shameful scam like so much else in this country.

“As has already been demonstrated in Australia, the only way a problem like this is solved is by the government stepping in and allocating responsibility, providing up-front funding and collecting contributions from those responsible.”

So far an untried ‘solution’ and one that does nothing to protect the tenant (or strata owner as is the case in Australia)

This quote below (from above) is relevant but must include the developer friendly tax hungry Government that made rip-offs normal business in this construction field.(in particular multi storey in OZ)

“A host of different professionals are responsible for designing and approving buildings constructed in this way.”

Too true but wno employs and pays for these professionals and who is it that comprimises them despite professional professed morality. It is of course the developer that these days can make more than 20% profitswhilst builders are lucky to make 3-5% (and nothing if the developer designs the contract and shifts all risk and responsibility for variations). Professionals often struggle too and are often pressured by the developers profit motive.

Governments have skin in the game as both Developers themselves and as recipients of largesse whether by taxation and building tithes or from developer contributions (official and unofficial)

It is quite clear that the developer should carry the risk of failed buildings (I believe in the ancient middle east in the event of collapse of a building the developer/builder was put to death) – a just reward for irresponsible and greedy behaviour and of taking advantage of lax regulation to blame others? The same applies for Government development but of course they also make the law!!