“It should never be forgotten that tribunals exist for users, and not the other way round.”

Carnwath LJ (as Senior President of Tribunals (UK)) at the Commonwealth Law Conference 2011

Part 1 of this guide is here

By Gill Nieuwland

Perhaps the best piece of advice I ever got from a solicitor about going it alone at the Leasehold Valuation Tribunal was: “Don’t!”

Naturally, I ignored him, and I’m guessing that, if you’ve come this far, (possibly having already ploughed your way through Leasehold Valuation Tribunal survival guides 1 and 2), you’re equally undeterred. Good for you. Without people like you, lay tribunals like the Leasehold Valuation Tribunal would not exist.

One reason legal professionals are chary of the Leasehold Valuation Tribunal, is the sheer unpredictability of the outcome.

The tribunal is known for its rather idiosyncratic flexibility. Essentially similar cases can produce wildly differing decisions.

Supposedly, its more laid back approach and relaxed rules were designed to make the tribunal more accessible to the litigant in person.

Actually, just the reverse is true.

What is most bewildering for the layman is not any complexity in the rules, but the seemingly arbitrary manner in which the tribunal applies them, and the fact that many of the layman’s professional opponents ignore them with impunity.

Now, however, some fairly earth-shattering changes are imminent at the Leasehold Valuation Tribunal, largely as a result of the Ministry of Justice’s desire to harmonise the rules across different types of first-tier tribunals to allow “more flexible deployment of judges and panel members across jurisdictions”.

It seems almost an unintended consequence of this administrative measure that leaseholder litigants bringing or defending a case after July 1 2013 also stand to benefit from the changes.

The new rules should introduce greater uniformity and rigour in case management and so help to eliminate some of the more scandalous imbalances unique to the Leasehold Valuation Tribunal where the lay leaseholder finds himself playing David to his freeholder’s Goliath. The Tribunal will be able to impose penalties for non-compliance with its directions.

Of course, it’s early days, so we can’t really make any assumptions about how things will play out, but at least there is now a framework for the Leasehold Valuation Tribunal to exercise real, grown-up case management powers.

From July, the Leasehold Valuation Tribunal will have a zippy new name, the First-tier Tribunal (Property Chamber) FTT(PC) in addition to the completely revamped set of rules.

Of course, to benefit from the new rules the leaseholder will first have find out what they are. My first port of call was the Leasehold Advisory Service, a “Non Departmental Public Body funded by Government to provide free advice on the law affecting residential leasehold property in England and Wales”.

It was disheartening to find them offering advice on the subject only via a £50 a head webinar which you’ll find here http://shop.lease-advice.org/products-page/webinar/learning-the-rules-of-the-new-first-tier-tribunal/#skip

I’m not buying it, on principle.

Also I’m hoping the Leasehold Valuation Tribunal will offer us a free pamphlet.

In the meantime, here are a few pointers from my own research as to how the lay leaseholder might use the new rules to his advantage. (All rule numbers refer to The Tribunal Procedure (First-tier Tribunal (Property Chamber) Rules 2013) http://www.legislation.gov.uk/uksi/2013/1169/pdfs/uksi_20131169_en.pdf

Directions

Gone are the days when your freeholder’s barrister could simply turn up to the PTR with a ready-made set of directions for a supine Tribunal to rubber stamp.

Rule 7 gives each party the right to ask the Tribunal to give specific directions, (you’ll also have to explain the reason) and to object to any directions proposed by the other side.

You may also challenge any direction made by the Tribunal, and apply to have it amended, suspended or set aside, while the Tribunal also may chop and change its own directions at any time, extend or shorten the time for complying with any rule, and consolidate different cases where there are issues in common.

The Tribunal may also permit or require a party to alter a document, require documents to be produced (see below) and direct that enquiries be made of any other person, and even hold a hearing to consider any matter, including case management.

Any party may also be required to say whether they intend to attend, or be represented at a hearing, whether they will be calling witnesses, and even, give an estimate for the length of a hearing.

All of this, if wielded effectively, could afford the litigant in person some of the comfort and protection he so desperately needs when faced with an unscrupulous (or just doing his job?) professional who knows the ropes.

How many times do you see witness statements appearing out of the blue at the last minute on the flimsiest excuse, gambling on the uninitiated leaseholder to let it stand?

One of the new rules needs particular caution as it may have potentially disastrous consequences for a litigant in person. We can only hope the Tribunal will be attentive.

The power to transfer proceedings to another court or tribunal if that court has jurisdiction, means that a case started in the Leasehold Valuation Tribunal could be transferred to a jurisdiction with a more onerous costs regime, so leaseholders may find themselves unable to pursue their case. That would be a pity. (see also “COSTS” below)

The Tribunal may transfer a case not only where there has been a change of circumstances since the proceedings were started so that the Tribunal no longer has jurisdiction, but also in a case where the Tribunal considers that the other court or tribunal is a more appropriate forum for that case. (Rule 6)

In general, the Tribunal will enjoy broad discretion as to the conduct or disposal of a case, and under Rule 8, will have greater flexibility in dealing with any party who fails to comply with directions or a requirement in the new rules.

The new arsenal includes asking the Upper Tribunal to exercise its superior powers in relation to a person who has not complied with any requirement imposed by the Tribunal.

Whether the Tribunal will actually manage to deploy any of these powers effectively against a freeholder, who for instance, claims to have “mislaid” an important document, remains to be seen.

Documents

In fact, as we’ve mentioned before, one of the main bars to justice at the Leasehold Valuation Tribunal for the leaseholder is the difficulty in getting hold of the evidence needed for the case. The freeholder holds all the documents and, despite s21 and s22 of the 1985 Act, which allow the leaseholder to obtain a statement of account and view all the supporting documents, many freeholders and managing agents are highly skilled in evasion tactics.

Having been party to three different Leasehold Valuation Tribunal cases in respect of the same major works consultation, I found in each case the Tribunal duly directed the freeholder to produce the estimates for the works.

Yet nothing was forthcoming until the third case, and even at that, only one estimate was grudgingly produced, literally days before the hearing, without so much as a murmur of disapprobation from the Tribunal.

Accompanying Tribunal directions, are Notes written in bold, warning that “failure to provide evidence as directed may result in the tribunal deciding to bar the defaulter from relying on such evidence at the hearing, and in the case of the applicant, in dismissal of the application”.

However, under the previous rules, this really seemed to refer only to applications considered frivolous or vexatious.

Legislation passed in 2002 (CLRA) would have made it “an offence” under the old regulation 22 for any party to withhold any information required by the Tribunal, subject to a fine of up to £1,000. To the everlasting shame of successive governments, this provision was never implemented.

The new rules are much more stringent and precise. The Tribunal (either on its own initiative, or at your instigation) may give directions as to the exchange between parties of lists of documents which are relevant to the application, or relevant to particular issues, and the inspection of such documents.

Alternatively, the Tribunal may provide for the disclosure and inspection of documents it considers relevant to the issues in dispute, (subject to certain conditions as to how those documents may be used) and, should a person fail to produce a document or facilitate the inspection of a document, the Tribunal may now refer to the Upper Tribunal to exercise its power.

(Rules 8 & 18) Fingers crossed!

Hopefully, a sensible use of these provisions would put paid to “document deluge”, another trick commonly used against a lay person, to force you to go to huge trouble and expense preparing bundles of completely irrelevant documents.

I know of one leaseholder who, having challenged three recurring items in the service charge going back over only five years, was presented with a freeholder bundle consisting of more than 500 double-sided pages, which she then had to copy and bind six times.

Summoning witnesses and orders to answer questions or produce documents

Another important breakthrough for leaseholders, is that, either on their own initiative, or at the request of any of the parties, the Tribunal may summon any person to attend as a witness at a hearing.

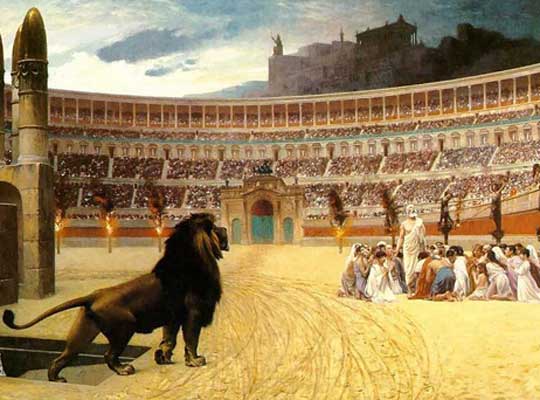

With any luck, this may deter your freeholder from turning up to a hearing, Roman emperor style, simply to enjoy the spectacle of an unfortunate leaseholder being mauled by their own savage counsel.

The freeholder now risks being subjected to the same treatment if you are lucky enough to possess that killer instinct, (and if not, you may now get someone better equipped to do the job for you! see below).

Incidentally, if you are getting a mauling from the freeholder’s barrister, ask the Tribunal for a break.

Don’t forget this is a property tribunal, not Guantanamo.

You can flounce out to their well-appointed bathroom, splash some cold water on your face, and come back fighting! A thermos of tea and a banana can do wonders for flagging spirits, when the hearing is dragging on interminably.

Leaseholders may now apply to the Tribunal to “order any person to answer any questions or produce any documents in that person’s possession or control which relate to any issue in the proceedings”.

This rule is likely to improve the leaseholder’s lot considerably (though it cuts both ways, of course!) and seems to embody such obvious good sense, that you may be astonished to learn that the Tribunal was previously unable to order anyone to answer to anything. (Rule 20)

Evidence

Under Rule 18, the Tribunal has broad powers to admit or exclude evidence. It may admit evidence that would not be admissible in a civil trial (the mind boggles, but perhaps one of our legally savvy readers can explain?) The Tribunal may exclude evidence where it would be unfair to admit that evidence, or where the evidence has not been provided in good time or in accordance with directions.

The Tribunal also now has the power to consent to or require a witness to give evidence on oath, which is a novelty.

However, there is no mention of the introduction of lie-detectors for the foreseeable future.

Expert evidence

The good news on this front is that you’ll no longer be confronted in a hearing with expert evidence that you have had no chance to examine.

Expert evidence cannot be included without permission from the Tribunal, and is to be given in a written report at least seven days before the hearing, unless the Tribunal decides otherwise.

The Tribunal may also limit the issues to be covered by the expert’s evidence, require her to attend a hearing to give oral evidence, and direct that the parties jointly instruct the expert.

On this last point, some caution is required, for presumably joint instruction will mean joint liability for costs, and to have an expert dance attendance at a lengthy hearing may be good for your case, but rather less so for your pocket. (Rule 19)

Representatives

You may appoint another person, whether legally qualified or not, to represent you in the proceedings.

You would need to notify the Tribunal and the other party in writing, giving the name and address of your representative.

From that point on, all correspondence between the parties would be conducted through your representative.

There is a new provision that you may also simply turn up at the hearing with another person either to represent you, or to assist you in presenting your case before the Tribunal, subject to the Tribunal’s agreement.

Apart from the benefit of having some moral support, two heads are better than one.

You no doubt have the advantage of intimate knowledge of the facts of your case, but your emotional involvement can cloud your judgement. The cool appraisal of a sympathetic but more objective person is invaluable, and probably much appreciated by the Tribunal.

Even if you feel you’d prefer to present your case yourself, try to get a spouse, sibling or a friend to accompany you. Very often you’ll find they can provide any number of helpful insights over lunch, but brace yourself for a critique of your performance.

(On second thoughts, it may be better to leave the kids at home!) (Rule 14)

Spurious applications

Sometimes a freeholder who knows he’s made a mistake, will try to catch the leaseholders off guard with a sneaky, disingenuous tribunal application say, over Christmas or the summer holidays.

When you receive Notice of an application, read it very carefully. The applicant will now have to give his reasons for making the application and the result he hopes to obtain. (Rule 26)

Withdrawal

The previous rules on withdrawal were particularly slippery, so it’s nice to have some clarity here.

It happens that an applicant freeholder, on receiving a statement of case from leaseholders, realises that he is going to incur (possible irrecoverable) costs for a case he is likely to lose.

He may attempt to withdraw the case, or at least a part of it. A case may be withdrawn orally at a hearing or by giving written notice of withdrawal to the Tribunal. First, copy of the notice must be sent to all other parties, and if any of the other parties consent, copy of their written consent must be sent to the Tribunal.

A point worth noting is that the Tribunal may make such directions or impose such conditions on withdrawal as it considers appropriate.

So even if you are content to have the case withdrawn, it may be worth asking the Tribunal to ensure that all relevant documentation is provided to you, as a pre-condition. You never know when you may need it!

And, in fact, any party which has withdrawn its case may apply for it to be reinstated within 28 days of the date of the hearing at which it was withdrawn, or, if within 28 days of sending a written notice of withdrawal to the tribunal.

The last part of this rule is a bit confusing (again we need expert advice) but it seems that even after a case has been withdrawn, any party may (within 28 days) apply for it, or any part of it to be re-instated. (Rule 22)

Striking out a party’s case

“Striking out” is a much more forceful expression than the “dismissal” referred to in the old regulations, and in fact, all budding applicants need to prick up their ears and pay attention here, for any proceedings or case, or the appropriate part of them will automatically be struck out if the applicant hasn’t complied with any direction for which it was explicitly stated that non-compliance by a certain date would lead to striking out.

The only other circumstances which must lead to striking out either of the whole, or part of a case will be when the tribunal does not have jurisdiction in relation to the proceedings and does not transfer the proceedings, entirely or partially, to another jurisdiction.

A subtle shift in emphasis in the following paragraph:

Having first given the parties an opportunity to make representations, the tribunal may strike out any proceedings or any part of them where the applicant has failed to comply with any direction for which it was explicitly stated that non-compliance by a certain date could lead to striking out. They may also be struck out if the applicant has failed to cooperate with the Tribunal so that it is impossible to deal with the proceedings fairly and justly, or

where the proceedings are between the same parties and arise out of facts that are similar or substantially the same as proceedings already decided by the Tribunal, they may be struck out, or

where the Tribunal finds any part of the case, or the manner in which it is being conducted to be frivolous, vexatious or otherwise an abuse of process, or where it considers any part of the application has no reasonable prospect of succeeding.

The applicant may apply in writing for re-instatement of a case, but this is restricted to those circumstances where he had been warned that failure to comply with directions would/could result in the proceedings being struck out. The usual 28 day time limit holds.

Of course, applicants do not have a monopoly on bad behaviour and respondents will also have to tread warily.

Under the new rules, they may now be debarred from taking part in the proceedings, or any part of them if they’re caught out indulging in any of the antics described above.

However, the respondent may also apply for the bar to be lifted, in the same way the applicant may request re-instatement of the case.

Unless and until the bar has been lifted, the Tribunal need not consider any of the respondent’s responses or submissions, and may summarily determine any or all issues against that respondent. (Rule 9)

Costs

The new provisions are both more detailed and wide-ranging than before. Leaseholders are going to need some high-quality legal resources on this, so please do send a link when you find anything useful.

The Tribunal may make an order for costs if a person has acted unreasonably in bringing, defending or conducting proceedings. So, though it hardly needs saying, be reasonable! (And since you are not a lawyer, you will probably know exactly what is reasonable and what is not reasonable, but don’t forget, you’ll still need to convince the Tribunal)

The Tribunal also now has full power to determine by whom costs are to be paid, and to what extent, in relation to “wasted costs” under section 29(4) of the 2007 Act. http://www.legislation.gov.uk/ukpga/2007/15/pdfs/ukpga_20070015_en.pdf

“Wasted costs” means any costs incurred by a party (so presumably including freeholder’s costs charged to your fellow leaseholders through the service charge)

- (a) as a result of any improper, unreasonable or negligent act or omission on the part of any legal or other representative or any employee of such a representative, or

- (b) which, in the light of any such act or omission occurring after they were incurred, the relevant Tribunal considers it is unreasonable to expect that party to pay.

This is an interesting development for the leaseholder litigant in person, because you will often find that the freeholder’s solicitor or barrister when confronted with a leaseholder will not hold himself to the same standard of professional conduct he would adopt vis à vis one of his esteemed colleagues.

The new provisions cover a good deal of ground, even after the fact, and this is something to underline.

As under the previous rules, the Tribunal may require a party to reimburse the whole or part of any fee paid by another party, either on its own initiative or at the request of one of the parties.

If you’re making an application in respect of costs, it’s probably a good idea to seek directions from the Tribunal as to how they intend to deal with the costs, and the format they require for details of the application.

The procedure for making an application for a costs order that is not made orally at a hearing is to send an application to both the Tribunal and the person against whom you are seeking costs. At this point, you may also send a schedule of the costs claimed, to allow the Tribunal to make an off the cuff assessment.

Presumably, in the case of the self-represented leaseholder that might include your travel expenses, time off work, stationery, sleeping pills, and hopefully a celebratory glass of wine …

The Tribunal may also order something to be paid on account, before it gets around to assessing the costs or expenses.

You may make an application for costs any time during the proceedings, but this must be within the usual 28 days after the date that the Tribunal sends out either its final decision, or a consent to withdrawal notice under rule 22.

However, the Tribunal can’t make any order for costs against a person unless that person has had a chance to make representations on the issue.

The amount of costs to be paid is determined by summary assessment by the Tribunal, or else by agreement between the parties, otherwise following detailed assessment of whole or part of the costs by the Tribunal or, if it so directs, by application to a county court on the basis specified by the Tribunal. (Rule 13)

When the Tribunal Procedure Committee put these new rules out for consultation, they made it clear that their aim was not to effect a material change in procedure but, rather, to provide greater flexibility in case management, considered desirable by the TPC.

However, like it or not, these rules do offer significant openings for the beleaguered leaseholder. It remains to be seen whether they will manage to turn these to their advantage, and the really gigantic unknown is how the ex Leasehold Valuation Tribunal now FTT(PC) intends to apply the rules. Over to them!

Note on transitional procedures

Any cases started before July 1 2013 and not yet determined will automatically fall under the new rules, with one key exception. Costs issues will continue as if under the old rules. It should be noted though, that the Tribunal has discretion to apply some of the old rules for “fairness”.

Look out for freeholders asking for dispensation from rule 8 should they happen not to disclose documents in time.

If you’re about to start a Leasehold Valuation Tribunal application you may want to wait until after July 1, so all the new rules will apply. Anyone with an on-going case needs to familiarise themselves with the new rules quickly or run the risk of freeholder’s counsel taking liberties.

Disclaimer

This article is in no way intended as professional advice, which I am not qualified to give. Please don’t rely on me! Always check with a solicitor, unless you’re a real die-hard DIY’er, in which case, you’ll find the new rules at this address

http://www.legislation.gov.uk/uksi/2013/1169/pdfs/uksi_20131169_en.pdf

Gill Nieuwland is a leaseholder in Kensington, London. Her website on leasehold issues is: www.termcontrol.co.uk.

© Gill Nieuwland June 2013

Second Christmas of misery for ‘squirrels in the roof’ leasehold owners

Second Christmas of misery for ‘squirrels in the roof’ leasehold owners

“More flexible deployment of judges and panel members across jurisdictions” having come accross Judges in the CC who were unaware of the LVT, and once explaining to one that “no the rent Act 1977 has not been repealed” this is fairtly scary propostion. Sadly panels arent all fully au fait with leases or simple accounting and its even more scary.

The quality of these posts is just excellent. We are preparing our case and will have to face the LVT in its new guise, and this guide, with Amanda Gourlay’s, is the best there is. Not just for laymen. Our solicitor has found this very useful as well. Many thanks for going to all the trouble to write this.

What I find really shocking is that, apart from Amanda Gourlay on “law and lease”, and this article, there is absolutely no advice available for leaseholders about the new rules at all.

And even now, we are still seeing LVTs that will not accept letters by email, although in two weeks time…….

i recently suffered a 2 day hearing at the LVT. J.freeholder created bogus invoices with little no details except repairs £1000+ even though the estimate for repairs was before the date i purchased the property the chairman insisted i was liable.

the j.freeholder also admitted the ‘uplift’ of a £1,000 on the builders bill was only notified to me by a ‘post it note’ on my door.

Luckily the £1k uplift was not considered. However, perjury is – the chairman shouted, “we have no remit for perjury, our remit is to stop people going to the civil court and save tax payers money”.

Be Warned – load up on lies and false invoices – the LVT is a ‘free for all – Kangeroo court. if you are honest – go to the Civil Court – it is the only place to be to get a fair hearing.